Close

The Belgian Waffle usually refers to the Brussels waffle, with its large rectangular shape, deep indentations and airy texture. Belgium's association with waffles is not that old. At the 1964 World's Fair in New York, fellow-countryman Maurice Vermeersch introduced the Brussels waffle as a national favourite. Even at later world exhibitions, such as Expo 2005 in Japan and Expo 2015 in Milan, the waffle was heavily promoted as a Belgian product.

There is no doubt that our medieval ancestors were already baking waffles. Waffles feature regularly in paintings by Joachim Beuckelaer and Pieter Brueghel the Elder, as well as on border miniatures in Books of Hours. There is also a drawing of a waffle baker attributed to Hieronymus Bosch, so that is around the late 15th century (Albertina, Vienna). In these paintings and drawings, waffles are associated with folk festivals such as Carnival, Shrove Tuesday and street fairs.

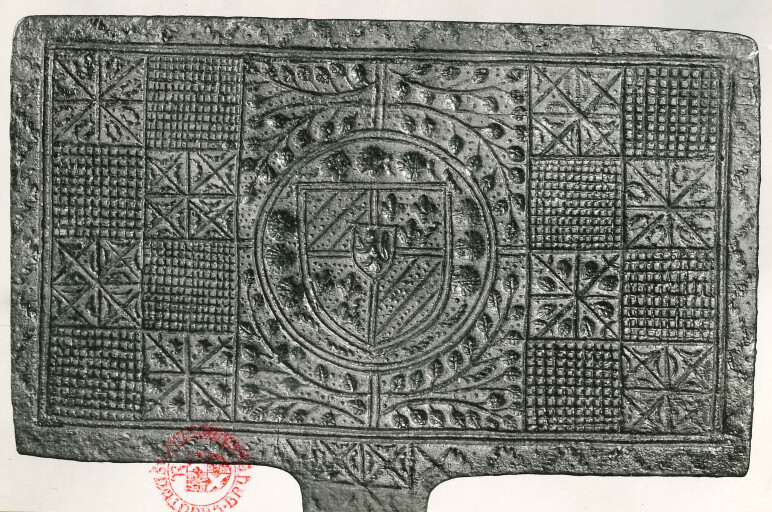

But the elite also liked their waffles. At least, that's what two 15th-century wafer irons in the Gruuthuse Museum's collection claim. They are among the oldest known wafer irons in the Low Countries and are decorated with the coats of arms of the Burgundian dukes John the Fearless (1371-1419) and Philip the Good (1396-1467).

The latest copy combines the coat of arms of Philip the Good with foliage (holly) and an image of the Mystic Lamb. Baking wafers was a typical Easter custom back then. Both the holly and the Mystic Lamb symbolise the Passion of Christ. As an evergreen tree, holly was associated with eternal life, while the prickly leaves referred to the crown of thorns and the red berries to the blood of Jesus.

The oldest copy boasts the coat of arms of John the Fearless on one side and a six-pointed star, or Star of David - a symbol used by both Jews and Christians - on the other. The border decoration here features geometric motifs.

Wafer irons were given as business gifts or wedding gifts. Are the wafer irons in the Gruuthuse Collection a gift from the Burgundian dukes to allies or to people in their entourage? We are left guessing. Either way, the rich decoration of the irons testifies to the sophisticated table culture of the Burgundian court. Like no other, the Burgundian dukes knew how to use gastronomy as a tool to demonstrate their power and prestige. The banquets they hosted overwhelmed not only with their overabundance of food but also with the imaginative table presentation. At the wedding of Charles the Bold in 1468, meat was presented in thirty table vessels bearing the arms, mottos and standards of the duchies and counties under Burgundian rule. It is not inconceivable that at such banquets, which sometimes lasted for days, wafers bearing the ducal coats of arms were also served as snacks or desserts.

Until the early 20th century, wafers were baked with tong-shaped irons. The iron was filled with a thin layer of batter and then held over an open fire with the tongs. Bakers had to mind their wafers, if not they would stick.

The Burgundian wafer irons from the Gruuthuse collection have shallow notches. This resulted in thin, crispy wafers, called oublies in French (from the Latin oblatum, meaning the gift of sacrifice). Sixteenth-century cookbooks, however, also turn up recipes for thick and airy waffles with diamond shapes, not unlike today's Brussels waffle.

In the Middle Ages, the new year began with Easter in many parts of Western Europe. With the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in 1582, New Year shifted to 1 January. The custom of baking wafers or oublies moved with it, and became a typical New Year's treat. In West Flanders, these New Year's wafers were coined as 'lukken'. Traditionally, children would go to congratulate - 'luk' - their godfathers or godmothers on New Year's day, and then these thin, crispy wafers would be produced. Lukken were prepared with a special 'luk' iron, made by the local blacksmith. Such irons were passed down from generation to generation as precious family heirlooms. One of those irons also ended up in the Gruuthuse Museum. It dates from the 18th century and bears the motto: ‘Ik wens u een zalig nieuwjaer.’ (I wish you a Happy New Year).

When biscuit baker Jules Destrooper from Lo-Reninge started producing these traditional New Year's wafers on an industrial scale in 1890, the West-Flemish lukken became known far beyond the provincial borders. West-Flemish expats also introduced this tradition to the United States. The Gazette of Detroit, a newspaper founded in 1914 that appeared in English and Dutch until the end of 2018, ran advertisements for Flemish luk irons every year in the run up to the New Year. Or how Belgian waffles and West-Flemish lukken conquered the world.